Fragments

Discovering the Power of What’s Been Lost

One of the unexpected delights from this reading project has been my encounter with fragments. Many ancient texts survive in full, but others survive in small snippets of text. This could be in the form of a physical fragment of a tablet or scroll or it could come to us in the form of an ancient hyperlink, a quote from another surviving work. For example, we know of lost Greek Tragedies because Aristotle mentioned and quoted them in his philosophical works.

I first encountered fragments in The Epic of Gilgamesh, the very first book I read as part of my Immortal Books reading list. There are portions of the story that have not survived. Translators typically identify where the text is missing by using an ellipsis (….) or brackets ( [ ] ). Smart people call these gaps “lacuna.” Here is an example from Gilgamesh:

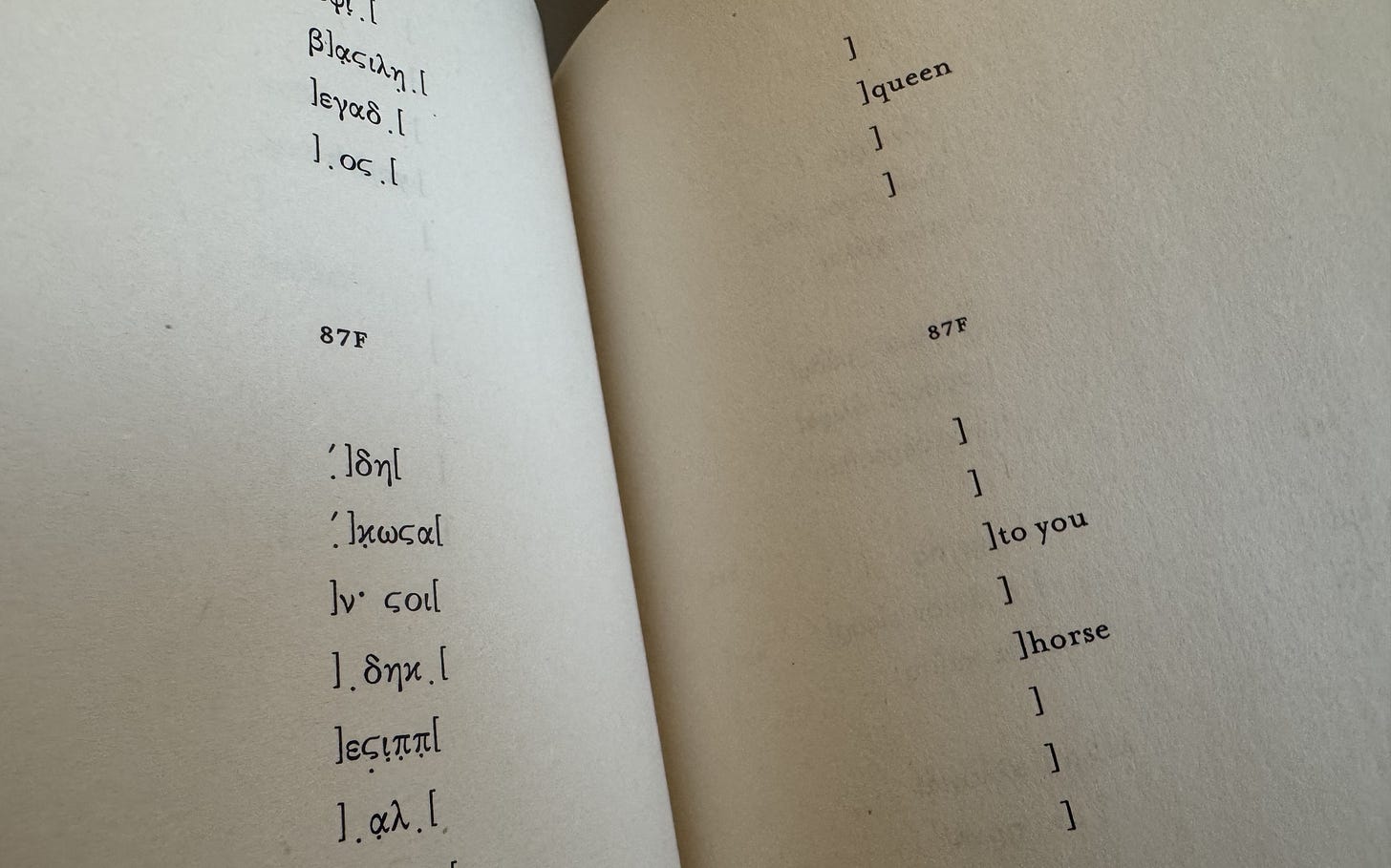

My next encounter with fragments came from reading Sappho, a Greek lyric poet. Some of her surviving poems contain just a few words (see below). At first, I wondered why a few words would be of any interest in preserving, but as I continued to read these fragments, I found my imagination becoming engaged in new and exciting ways. I would wonder what the poem was about and would even attempt to fill in the gaps with my own words, as if it were some sort of ancient Mad Libs.

After Sappho, I read Homer’s Iliad. I was surprised that the epic did not contain the stories of the kidnapping of Helen, the Trojan Horse, or the death of Achilles. It turns out, those parts of the story were included in other works that were part of a Trojan Epic Cycle. That cycle contained 8 total works, of which only two survive (The Iliad and The Odyssey). There was a work that preceded The Iliad and that contained the story of the kidnapping of Helen and there were works between The Iliad and The Odyssey that contained the stories of the Trojan Horse and the death of Achilles.

I purchased the Greek Epic Fragments from the Loeb Classical Library and that book highlighted the missing works and what was in them (they were not all written by Homer). The ancients would have known the entire epic cycle. What we know of them comes to us in fragments.

After Homer, I began reading the entire set of surviving Greek Tragedies. I learned that a small portion of the overall tragedies survive (a tragedy in itself). For example, Sophocles is thought to have written more than 100 tragedies and yet 7 survive in full. The rest come to us in fragments. The Loeb Classical Library has a work or two for each of the tragedy writers. This allows us to see all of the different tragedy plays from each playwright. It’s a fascinating look at their entire corpus. My favorite part is reading specific quotes from a tragedy play that has not survived and wondering what the context was, who said it, and how it fit into the play as a whole.

We’re very fortunate to have the number of surviving texts that we do. We owe a debt of gratitude to the scholars and scribes through the ages who painstakingly copied these works. Some survived; many didn’t. We’re still discovering fragments and works and a number of clay tablets sit in museums waiting to be read and translated by scholars. It’s a truly exciting time to be alive. These fragments point to marvelous stories, poems, and knowledge that point to lost treasures.

If you’ve never experienced the joy of reading fragments, start with one of the works mentioned above. You’ll find your imagination sparked in new and exciting ways.

Thanks for sharing portions from your physical copies - it's helpful to see how certain books actually look.

This was delightful to read! A big riddle for me is, how much value can we accurately assign the existing works we have when we don't know have access to the rest? Of course, it's impossible to know. It's just interesting to think, for example, that we see the Odyssey and the Iliad as these masterpieces when perhaps their missing counterparts are even better. Or maybe not better, but just different in ways we can't imagine.