Freedom in a Gulag

Imagine being able to say this: “Bless you, prison!” … I nourished my soul there.”

This article contains one of the most important ideas I’ve come across in the past 7 years of this reading project. It centers around a question I’ve held since childhood—who survives hell on earth (in the form of a concentration camp, slavery, or a gulag)? Put another way, what type of person or what characteristics does a person need to embody to survive the worst that other people can do to them?

I found answers to this question in three different books. These works were forged through intense suffering by the authors:

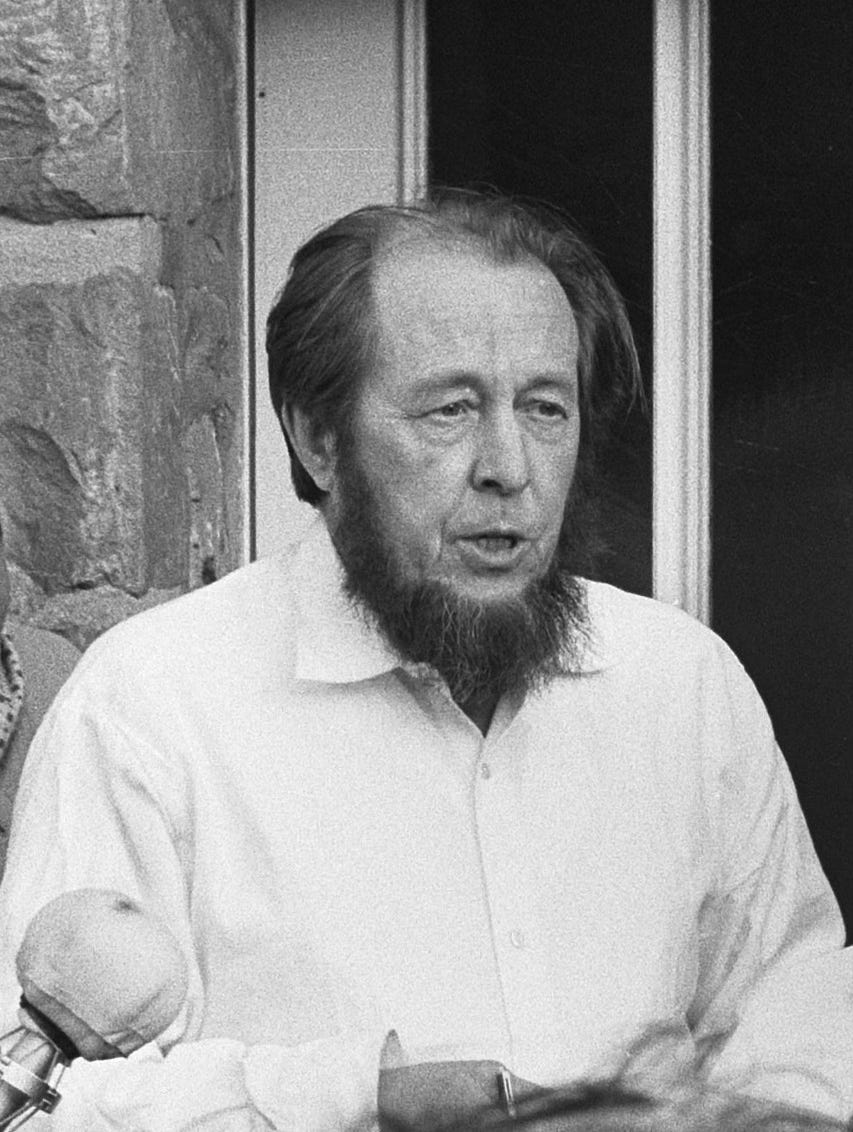

The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

In this article, I’d like to focus on what I learned from Solzhenitsyn. I was stunned by his answer to my life-long question.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn spent 8 total years in the Soviet Gulag (1945 - 1953) for criticizing Stalin in a letter to a friend. He experienced firsthand the horror of the Gulag. Years later, he made the following statement:

And that is why I turn back to the years of my imprisonment and say, sometimes to the astonishment of those about me: “Bless you, prison!” … I nourished my soul there.

Can you imagine being able to make that statement? Think back to the absolute worst experience of your life. Do you say you nourished your soul there?

Conditions alone killed a number of people in the Gulag prison system. It was hell on earth. A daily source of humiliation, hunger, cold, torture, and forced labor.

When picking up The Gulag Archipelago, I expected to read about horrifying atrocities. And I did. I expected to find a bitter man who had somehow survived hell and was writing to tell just how bad it really was and just how bad they really were. But I didn’t.

Instead, I found a man talking about his soul and the souls of those around him. I found a man comparing his soul to that of his guards. To an outside observer, the guards were the fortunate ones. They had power, food, warm clothes, and a chance for advancement. But they were missing something:

…the meaning of earthly existence lies not, as we have grown used to thinking, in prospering, but…in the development of the soul. From that point of view, our torturers have been punished most horribly of all: they are turning into swine, they are departing downward from humanity.

So how does this relate to my original question of who survives the Gulag? Solzhenitsyn continues:

…those people became corrupted in camp who had already been corrupted out in freedom…Because people are corrupted in freedom too, sometimes even more effectively than in camp.

The people who survived the Gulag were becoming the type of people who could survive long before they ever arrived at the Gulag.

That answer provided me with so much hope. It meant that you and I can become the type of people who can weather coming storms. But the decision to do that begins today, not in some idealized future in which I do the right thing in the worst of circumstances.

This is one of the most profound ideas I’ve come across in this reading project. That small, seemingly insignificant, and oftentimes unseen decisions matter a great deal. Those decisions set a path for a life. They set a path that can continue right through hell on earth. But the path won’t magically appear in hard, life or death situations. That path must be practiced day by day, decision by decision.

Oh may we be the type of people who look back on our lives and say “I nourished my soul there.”

Thank you. I really needed to read this today. I too ask this same question. Resilience, true character, how to look beyond the circumstances I am in and grow. As a Christian, God’s word asks and answers some of these same questions. But your reflection on “Freedom in a Gulag” offers fresh meaning. Meaning, I am thankful for! Love this post.