The Dividing Line

Solzhenitsyn & Frankl on Good vs. Evil

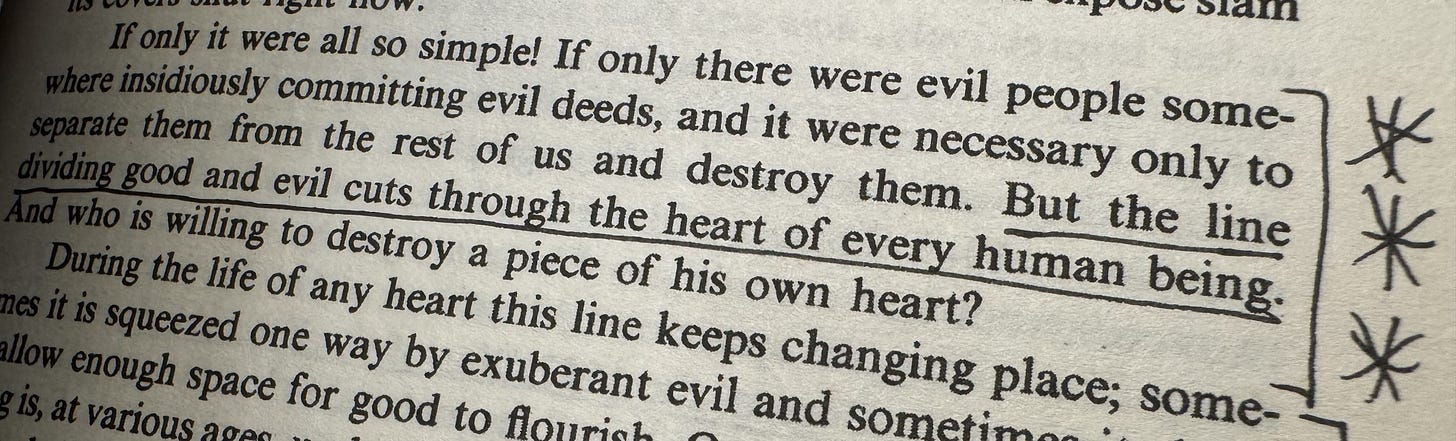

I have an extensive markup system I employ while reading books. I underline key phrases, write notes on the inside back cover, and place stars ⭐️ beside really important content. Within the star system, I use one star for something with more importance than a mere underline and two stars besides ideas that are truly amazing. It has not happened often, but there are a handful of occasions where I’ve gone so far as to place three, yes three stars next to life-altering content.

In a 2019 reading of The Gulag Archipelago by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, I granted 3 stars to the following passage:

“If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”1

Viktor Frankl, a survivor of multiple concentration camps during the Holocaust, said nearly the exact same thing 27 years earlier in Man’s Search for Meaning:

“The rift dividing good from evil, which goes through all human beings, reaches into the lowest depths and becomes apparent even on the bottom of the abyss which is laid open by the concentration camp.”2

The reason this idea struck me so deeply was because the line dividing good and evil seems to be crystal clear in the case of a Nazi prison guard. They are the evil ones who should be separated and destroyed. And yet, here are two prisoners of atrocious torture camps writing that evil is not just a problem for the prison guards but can be found in their hearts as well.

To be clear, Solzhenitsyn and Frankl were not proposing a moral relativism that excused the evil. They merely acknowledged the propensity for both good and evil in the best and worst of humankind. Despite the propensity, there was a clear difference in the direction of the soul. Solzhenitsyn wrote:

“…the meaning of earthly existence lies…in the development of the soul. From that point of view our torturers have been punished most horribly of all: they are turning into swine, they are departing downward from humanity.”3

And Frankl distinguished between the race of decent men and indecent men, placing nearly all of the guards on the indecent side.

The idea that the good/evil dividing line cuts through every human heart is not new. Neither is the urge to round up the bad ideas, elements, and people to destroy them in the belief that a utopia will ensue. The Us vs Them tribalism is intoxicating. But that is hard to maintain if the line dividing good and evil cuts through my heart and your heart.

Later on in The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn expands on his earlier quote:

“Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains... an unuprooted small corner of evil.”4

This is a message for our time. It should humble us as we pursue the good, true, and beautiful. As a character stated in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, “The awful thing is that beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the devil are fighting there and the battlefield is the heart of man.”

May we be those, who like Solzhenitsyn amidst hell and suffering, could say of his time in prison, “I grew my soul there.”

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, abridged ed. (London: Vintage Classics, 2003), 75.

Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, trans. Ilse Lasch, rev. ed. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006), 87.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, abridged ed. (London: Vintage Classics, 2003), 310-311.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918–1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, abridged ed. (London: Vintage Classics, 2003), 312.

I just read a little Tolstoy and Dostoevsky this week, and there is something indispensable about the Russian pathos that extends to Solzhenitsyn. We need their window on the world, almost as an antidote to our clinical modernism that at its core wants to reject even the idea of a soul. And Frankl proves that it’s not just the Russians. Thank you for this post today.

Thank you for the lively discussion last night on Man’s Search for Meaning! I have sent the book to my three daughters who are all in their 20’s. Luckily, they are all very interested in what a holocaust survivor would have to say about the meaning of life or finding meaning in one’s life. I think it’s crucial for one to find meaning in one’s life, so I am thrilled to have my girls read Frankl’s theory and life experience. There is so much that can still be said on this book and perhaps the discussion continued well after we had to leave. I love hearing about your connections to the Gulag Archipelago and am interested in that as well if I can struggle through the horror but also looking forward to White Nights. Thanks again!