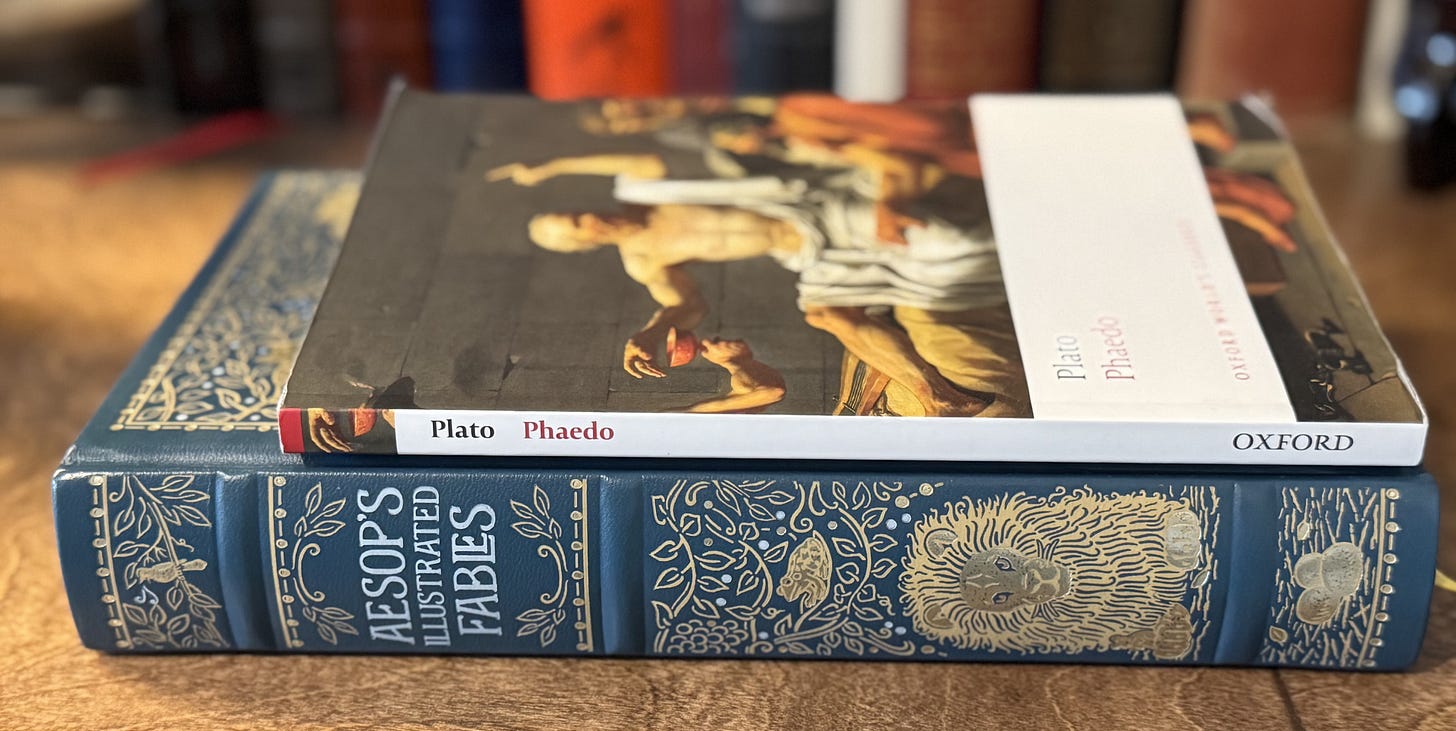

There’s a short, delightful aside at the beginning of Plato’s Phaedo. The dialogue famously ends with the death of Socrates after he’s led a fascinating discussion about the soul. As his friends arrive to comfort him on this most fateful of days, they encounter Socrates at peace, focused on the most unexpected of activities.

He is setting Aesop’s Fables to verse.

He’s taking well-known tales and writing them out as poetry.

Why? Why would he do that with mere hours of life remaining? And why poetry?

Socrates’ life was one of prose. That may be an odd way of considering his work, but his oral dialogues and arguments were conducted in ordinary language without meter. Greek philosophers, though indebted to the poetry of Homer and the tragedians, considered prose a superior medium in which to communicate truth.

Yet Socrates never wrote down his arguments. They were all conducted orally. Plato, his student, left us with 30+ Socratic dialogues. So it’s quite odd for the most famous philosopher in history to spend his final moments physically writing in elevated language set to meter, i.e., in poetry.

In Phaedo, Socrates tells about a recurring dream from earlier in his life where he was told to “make art and practice it.” He had considered his life’s work a fulfillment of that instruction because “philosophy is a very high art form.” Yet he continues:

“I reflected that a poet should, if he were really going to be a poet, make tales rather than true stories; and being no teller of tales myself, I therefore used some I had ready to hand; I knew the tales of Aesop by heart, and I made verses from the first of those I came across.”1

I wonder if this little vignette is a sort of foretaste of the main argument found in Phaedo. Socrates argues for the existence of a soul because learning consists of recalling the Forms on earth. Socrates has seen the otherworldly Form or Idea of Beauty in earthly art, people, and nature. Those lower-case instances of beauty have pointed to Beauty.

In a way, Aesop’s Fables are a Form. They are well-known stories in circulation. They are capital letter Fables and Socrates is creating a lower-case poetic fable. He’s versifying it. And he’s presumably leaving these poems of fables with his friends.

A man who dedicated his life to oral prose closes out his final moments with written poetry. Ironically, it’s the oral prose that has survived through Plato. Oh that these verses had been passed down to us for us to read the poems of Socrates.

While reading Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning this morning, I came across the following story. Amidst the horror of the concentration camp, Frankl tells of a woman who knowing she was about to die, died with inner greatness. He said her death “seems like a poem.”2

Socrates’ use of the last few hours of his life is a thing of Beauty.

Plato, Phaedo, trans. David Gallop (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 5.

Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, trans. Ilse Lasch (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006), 69.